There are times in life, all too often in fact, when you find yourself looking up at a very long climb. The metaphor has been woven into the sermons of Miley Cyrus and Robert Frost alike, life’s a climb, a journey of many miles, miles to go until we sleep.

Endurance pursuits are, for me, a process of contextualization for the grander journey of life. If I can run 46 miles today, if I can battle through the long stumbling slogging lows and appreciate the wild rushing joy of the highs, maybe I can do the same in real life too. I think there is so much to learn from long distance hiking and running, because they are these amazing little handheld model-sized versions of the bigger rollercoasters we face in life. They help me understand the meaning of really hitting rock bottom, as well as the real possibility of digging yourself out again, bit by bit, mile by mile. It’s not the only reason I love going farther, longer, deeper, but it’s a big part of it.

Last summer, after finishing the Hayduke Route, I signed up for an ultramarathon. Maybe I felt the need to finish something really challenging after not completing the Hayduke Route as I’d initially planned, but it was a something I had been interested in doing for a while. My dad is a runner, and watching him train for and run big races like the Leadville 100 Mile Run made ultrarunning seem like a normal, or at least fully rational and attainable thing. I always figured I’d try one myself eventually. I have been a runner for my whole life, and last summer the timing was finally right to try something big. I chose an ambitious goal (not surprising): a 105k race in the Elk Mountains just north of Crested Butte, called the Crested Butte Ultra. It had about 15K feet of climbing along the route and topped out an an elevation of 12,300 feet above sea level, a relatively gnarly creature.

I didn’t finish it. DNF’d as they say in the running world. Dropped out, just like the Hayduke. But really, that was only the end of a much longer story, that was full of real accomplishments that I am still quite proud of. Maybe that’s the other thing I love about long distance running… it is so much more than the race. It is a thread that stretches across the season from end to end and weaves its way through every incredible mile (and every shitty one). I guess for me, it’s not just about those last insane 30, 50, 65, or 100 miles. It’s really about the other 1000 miles it takes to even step up to the start line.

Because of this, I wanted to go back and revisit some of my favorite moments from my training. I want to allow myself to hold them up to the light as self-contained accomplishments. At the very least, I want to show off some nice pictures from nice places that I took while feeling like roadkill put through the wash.

Early Stages: Re-Building a Long-Neglected Base

I’ve talked about this process in a previous post, but a quick recap. After discovering some lurking knee issues while hiking the the Colorado Trail in 2016, I took a lot of time off from running. The following summer, I wanted to try running an ultramarathon but, I soon realized it would take longer than a year to rebuild my fitness and endurance. After getting off the Hayduke Route, I had enough of a base to begin ramping up for some serious training.

I was living at my parents’ house at this point, which is about as well situated for spring running as a place could be. I had just about endless options for 4-15 mile runs within a few minutes of home, like Staunton State Park, with it’s big granite cliffs…

and Bergen Peak with it’s long, steady climbs…

and the toes of the Mount Evans Wilderness.

Even running around the neighborhood was pretty pleasant.

Dangerous skies near the end of my first marathon

Dangerous skies near the end of my first marathon

After a couple months of ramping up, I began to run longer distances than I’d run in a single day before. This is where the process went from just running, to really learning and finding my way into new territory. I had my first bonking experience in the Flatirons near Boulder, CO. The day started nicely, but it went downhill on the last major climb. I felt the deep exhaustion creep in along with vague nausea and lightheadedness, but I kept pushing, not knowing how much worse the feeling could get. After summiting the last peak of the run, I collapsed on the descent. I was able to haul myself into a shady place where I could sit safely, but it was almost an hour before I could stand again and stumble the last 4 miles to my car. A harsh lesson, but it had to be learned eventually.

The metabolic crash known as the bonk would haunt many runs that season, though none would be quite so dramatic as that first experience. Some people don’t really deal with bonks much, usually people who have no trouble eating while running, or that handle the heat well. I don’t fit into either of those categories.

My next majorly challenging run was when I accidentally ran my first marathon. I went down to a nearby section of the Colorado Trail for what I expected to be a 21-22 mile run on a hot day. I thought I was pretty well loaded up with salty snacks and fluids, but I still ran out of water around mile 19, when I thought I had about 3 miles left. Not too bad, I figured, I could power through 3 miles. Little did I know, the trail had been re-routed so the distance I had measured from the map was inaccurate. I ended up running 7 dry miles, 26 miles total. When I finally got back to my car, I just laid on the ground for half an hour, sipping little bits of water, as much as I could keep down. Eventually, a couple mountain bikers rolled up and noticed me as they loaded their bikes into their decked-out Tacoma.

“Hey,” one said, sounding more than a little concerned, “do you want a cold beer?”

I almost kissed him on the spot, but instead I just sat up and nodded and thanked him as best I could for what was likely the best beer I’ve ever had: a slightly-cooler-than-room-temperature Coors Light. I should note that usually I can’t stand Coors, due to living traumatically close to the massive brewery as a kid.

Another lesson learned, more water, more salt, heat is a game-changer. I would continue to learn these lessons bit by bit as I ran further, longer, harder.

Soon though, I would be leaving this little mountain running paradise for a much stranger place.

The Meat and Potatoes: Long Miles in Northern Arizona

After a very neat family trip to Italy, I packed up my truck and drove for 12 hours to my home for the rest of the summer: the Grand Canyon. In its own right, this was a wild and really wonderful experience, but training here was a lot more challenging that I expected it to be.

Running in the Grand Canyon has two modes: mostly flat to slightly rolling trails above the rim, and relentlessly steep grades below the rim. I tried to mix up my shorter runs, alternating between moderate cruiser runs and tough dusty steep runs. The trouble was the longer runs. I could put as many miles as I wanted onto the lovely singletrack of the Arizona Trail, but it didn’t have the vertical I needed, and going into the Canyon would require running in 90-100 degree heat, which was pretty much a showstopper.

I also needed to train at higher elevations, ideally 10,000-13,000 feet above sea level. The nearest option that would provide the vertical, elevation, and relief from the summer heat was the San Francisco Peaks area near Flagstaff. It was a solid 4 hour drive, but that didn’t seem so terrible when I had to drive 1.5 hours to get groceries every week anyway.

It felt amazing to get up high into the cooler wetter mountains. I really enjoyed my time in the San Francisco peaks, but I didn’t make it down to them often enough. About half of my long runs were flatter runs on the North Rim. The fact that I couldn’t consistently train for hard climbs at high elevation had me feeling vaguely concerned and antsy for much of the season. Would it be enough training for me race?

A Gem in the San Juans

As I neared the peak of my training, I decided I needed at least one long run with an average elevation above 11,000ft. I packed my running stuff, some food, and a six-pack of cheap beer into my truck and drove 7 hours to the core of the San Juan Range in Southwest Colorado.

I woke up in my truck, the condensation-covered windows blurring the views if the surrounding mountains in the early dawn light. I fumbled to pull on my running shorts, cold trail shoes, and running pack. I loaded up with water and gels and such, tucked my keys into my waistband, and started my watch as I stiffly half-jogged up the trail.

The day would turn out to be incredibly pleasant. My run was mostly on one of my favorite sections of the Colorado Trail. Clouds floated quietly across a deep blue sky, and the mountains glowed green and grey and orange in their mid-summer glory. It wasn’t my fastest run, but it was probably my favorite that season.

I’m proud of all I learned last season, and I’m excited to try another 100k this summer. I’ll post Part 2, which talks about my two biggest runs last summer (the Grand Canyon Rim2Rim2Rim, and the Crested Butte 100k race) soonish. Keep a lookout, and thanks for reading!

The most photographed North Rim view

The most photographed North Rim view Late afternoon light on the North Kaibab Trail

Late afternoon light on the North Kaibab Trail One of many views from the Walhalla Plateau

One of many views from the Walhalla Plateau This arch, Angel’s Window, is visible from the Colorado River, thousands of feet down.

This arch, Angel’s Window, is visible from the Colorado River, thousands of feet down.

The last of the Sun’s light ignites fire in a late evening thunderhead.

The last of the Sun’s light ignites fire in a late evening thunderhead. Rosey hues on stunning views

Rosey hues on stunning views Even on smokey days like this, the sunsets at my favorite evening beer spot were wonderful.

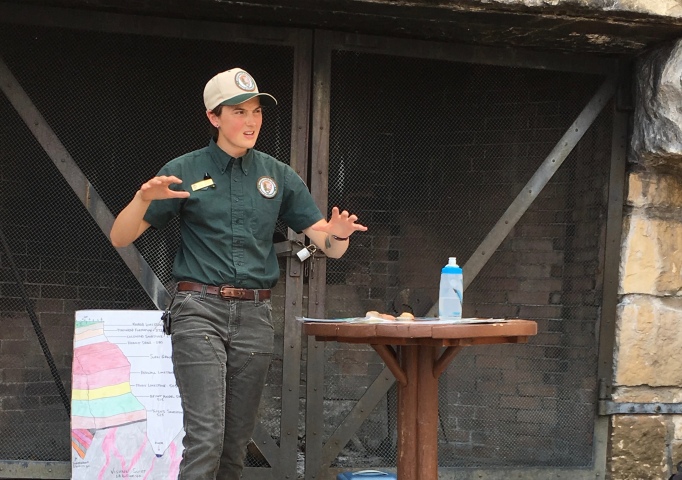

Even on smokey days like this, the sunsets at my favorite evening beer spot were wonderful. “Ancient swamps and tidal flats”

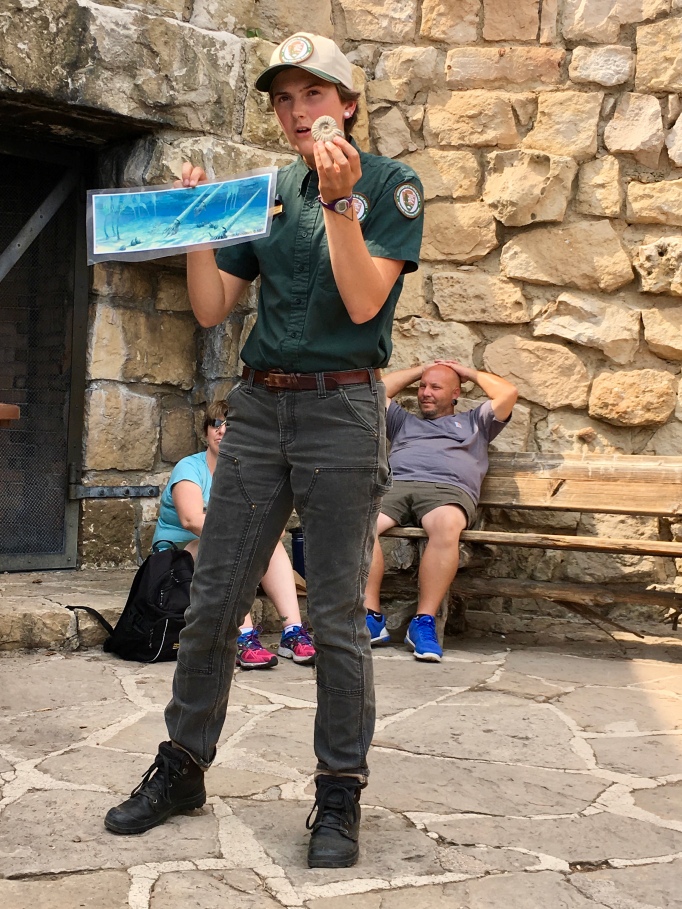

“Ancient swamps and tidal flats” “Ammonites once roamed these shallow seas that would become Grand Canyon”

“Ammonites once roamed these shallow seas that would become Grand Canyon” An afternoon storm rolls and roars over the South Rim, over 10 miles away.

An afternoon storm rolls and roars over the South Rim, over 10 miles away. Lightning strikes to the West at dusk

Lightning strikes to the West at dusk The long approach to Marion Point involved following the narrow and subtle Nankoweap Trail. The point is visible in the center-left of this picture.

The long approach to Marion Point involved following the narrow and subtle Nankoweap Trail. The point is visible in the center-left of this picture. The Nankoweap precariously winds along a soft layer of rock, with steep cliff bands above and below

The Nankoweap precariously winds along a soft layer of rock, with steep cliff bands above and below Once one leaves the trail, the adventure begins. There was some nice 4th class scrambling on loose rock. At this point in particular, the bottom was a loooong way down.

Once one leaves the trail, the adventure begins. There was some nice 4th class scrambling on loose rock. At this point in particular, the bottom was a loooong way down.

Shelves and ledges

Shelves and ledges A layer at the head of the canyon was rich with fossils, like this one, perhaps a spiny brachiopod?

A layer at the head of the canyon was rich with fossils, like this one, perhaps a spiny brachiopod? Near river level, the drainage-bottom constricted into narrows in the Tapeats Sandstones, a neat, multicolored later in the Grand Canyon

Near river level, the drainage-bottom constricted into narrows in the Tapeats Sandstones, a neat, multicolored later in the Grand Canyon

A novel mix of vegetation, with sharp agaves and yuccas that I hadn’t seen before (left), as well as soft, water loving plants I knew from Southern Utah’s damper canyons (right).

A novel mix of vegetation, with sharp agaves and yuccas that I hadn’t seen before (left), as well as soft, water loving plants I knew from Southern Utah’s damper canyons (right). At camp, watching light from a setting Sun on Holy Grail Temple

At camp, watching light from a setting Sun on Holy Grail Temple A rare selfie

A rare selfie The clear, cool magic of Shinumo Creek, with King Arthur Castle illuminated in the background

The clear, cool magic of Shinumo Creek, with King Arthur Castle illuminated in the background Visiting the Glen Canyon Dam… yuck. I didn’t enjoy this one so much.

Visiting the Glen Canyon Dam… yuck. I didn’t enjoy this one so much. Running up Humphreys Peak, the tallest mountain in Arizona. It was a rainy, cool day and I felt like I was in Washington, not the desert southwest. This was part of my training for an ultramarathon… more in that in another post

Running up Humphreys Peak, the tallest mountain in Arizona. It was a rainy, cool day and I felt like I was in Washington, not the desert southwest. This was part of my training for an ultramarathon… more in that in another post On a clear day, you can see all the way to the North Rim from Humphrey’s 12,633ft summit

On a clear day, you can see all the way to the North Rim from Humphrey’s 12,633ft summit The 4 hour drive to Humphreys, Flagstaff, and the South Rim involves crossing the Colorado River on Navajo Bridge, below the endless Echo and Vermillion cliffs

The 4 hour drive to Humphreys, Flagstaff, and the South Rim involves crossing the Colorado River on Navajo Bridge, below the endless Echo and Vermillion cliffs A river in chains, but not forever. She carved through thousands of feet of rock, and no dam will hold her

A river in chains, but not forever. She carved through thousands of feet of rock, and no dam will hold her Lake Powell was a strange experience for me. The green water against the orange cliffs is striking and at times objectively beautiful, but the knowledge of what was lost in the creation of this place is heartbreaking.

Lake Powell was a strange experience for me. The green water against the orange cliffs is striking and at times objectively beautiful, but the knowledge of what was lost in the creation of this place is heartbreaking. Lower Antelope Canyon is accessed right from Lake Powell, so you have to paddle to it.

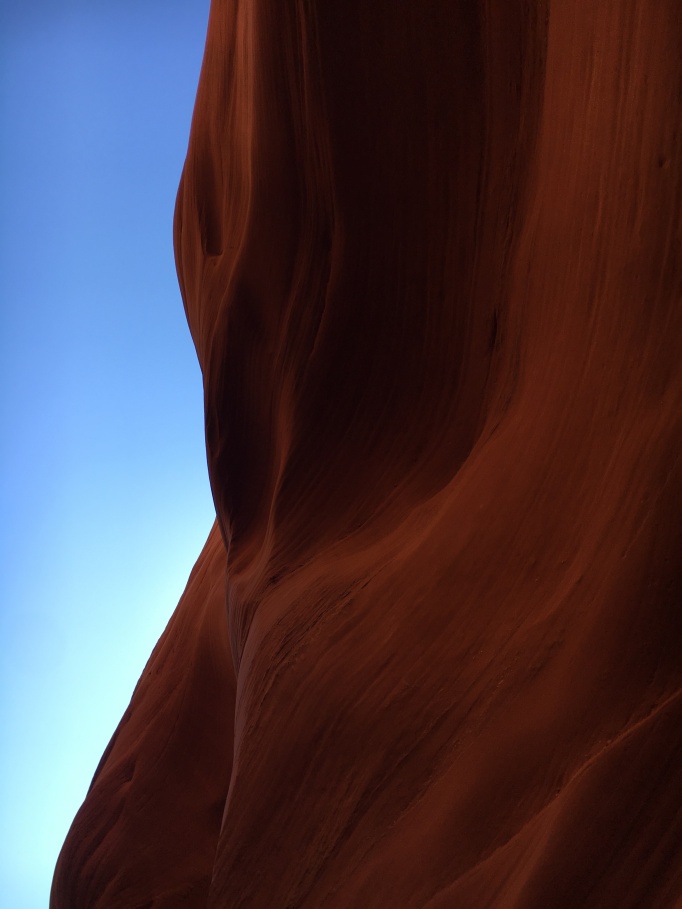

Lower Antelope Canyon is accessed right from Lake Powell, so you have to paddle to it. Volumes unspoken, but keenly felt

Volumes unspoken, but keenly felt An especially hot weekend brought me to the cool depths of Zion National Park’s canyons. Soon to come: a post about my first attempts at canyoneering here

An especially hot weekend brought me to the cool depths of Zion National Park’s canyons. Soon to come: a post about my first attempts at canyoneering here Where water is wealth, this place is almost ostentatious

Where water is wealth, this place is almost ostentatious Aspen leaves

Aspen leaves I couldn’t get any good shots of the real birds because they were so far away, but this sign helps conceptualize their insane wingspan.

I couldn’t get any good shots of the real birds because they were so far away, but this sign helps conceptualize their insane wingspan. Cliffs and clouds

Cliffs and clouds I spoke with an older gentleman for over an hour on this overlook about expectations and gratitude. It was strangely fitting for my last day of work.

I spoke with an older gentleman for over an hour on this overlook about expectations and gratitude. It was strangely fitting for my last day of work.

a mouthwatering route

a mouthwatering route

Hut #3 from the top of Via Ferrata #1

Hut #3 from the top of Via Ferrata #1 Sophie, my sister, being a complete badass

Sophie, my sister, being a complete badass

Spot the humans?

Spot the humans?

Spot the hut!

Spot the hut!

The hike out

The hike out Towering walls

Towering walls

Somewhere to eat lunch

Somewhere to eat lunch

The crane really rounds out the cultural experience.

The crane really rounds out the cultural experience.

powder-covered bumps

powder-covered bumps looking back up into the North Bowl

looking back up into the North Bowl The top of the North Bowl, only accessible via a long, conga-line boot pack, but sooo very worth it

The top of the North Bowl, only accessible via a long, conga-line boot pack, but sooo very worth it

The chutes off of Gracias Ridge

The chutes off of Gracias Ridge Cinco Chute was fun, but Tres was my favorite

Cinco Chute was fun, but Tres was my favorite The boot pack

The boot pack The view at Lake Louise

The view at Lake Louise Bare larches

Bare larches The view from the Goat’s Eye lift at Sunshine

The view from the Goat’s Eye lift at Sunshine Some fun chutes at Sunshine, with a little soft, wind-deposited snow

Some fun chutes at Sunshine, with a little soft, wind-deposited snow